On Thursday, December 3, 2015, students from TC Williams High School in Alexandria, Va., took part in a Traveling Forensics Lab session, taught by the National Law Enforcement Museum. A teacher at the school set up this forensic activity to have the STEM and Criminal Justice students participate.

Students were able to recreate blood stain patterns made by three different tools in the lab. They were then able to compare the blood stain patterns to those found at a crime scene. Students also used magnetic powder to dust and lift their own fingerprints. They were then able to classify their prints into three categories, loops, arches, or whorls. As part of the experience, they were able to read and verify a suspect’s alibi by looking at their call logs.

This multi-station Traveling Forensics Lab introduces students to forensic science. Students step into the shoes of crime scene investigators to solve a case. The course offers five core workshops that provide the key elements of forensic science and expose students to potential careers in forensics. These workshops were developed to meet the needs of 5th through 12th grade students, but can be tailored for any audience.

If you’re interested in hosting this or other forensic labs for your students, you can contact our educator at 202.737.7860 or education@nleomf.org. You can also look at our Frequently Asked Questions.

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

Thursday, October 15, 2015

The Great Magician’s Escape

In 1906, the District of Columbia played host to “Handcuff King,” Harry Houdini. The great magician and his wife were visiting Washington, DC for Houdini’s performances at the Chase Theater when Metropolitan Police Chief Major Richard Sylvester invited the escape artist to test the Metropolitan Police’s metal. Sylvester, a leader in American policing, was eager to show off his newest station house built in 1901. The Tenth Precinct’s Lieutenant explained that the station house boasted, “…cells of the most modern and approved pattern. The doors of these cells are steel-barred and have the most intricate combination locks.”

Houdini arrived on January 1, 1906 to the Tenth Precinct to examine the jail cell and locks before the escape. Once he was ready, Houdini was searched, stripped, and placed in cell 3 while his clothes were placed in cell 6. Then, the police officers changed the game. Houdini remembered, “I heard [the police lieutenant] whisper to one of his men to bring him the locks for another cell.” With his pride and reputation on the line, Houdini went on with the trick knowing the stakes had been substantially raised. Houdini later said, “I took a long chance there.”

|

| Officers and Members of No. 10 Precinct |

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

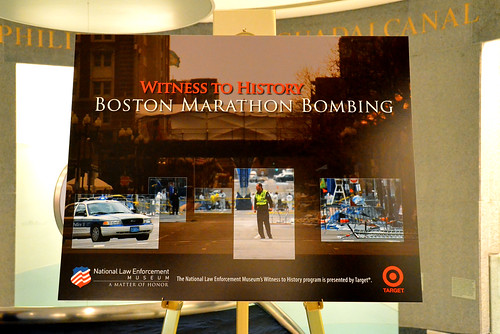

Witness to History: Boston Marathon Bombing

National Law Enforcement Museum’s Panel discussion examined the events of the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombing investigation and its impact on the community.

It was only two and a half years ago on April 15, 2013, that two explosions at the finish line of the Boston Marathon shook the nation and changed the lives of so many. On Wednesday, October 7, 2015 the National Law Enforcement Museum brought together Richard DesLauriers, former Boston FBI Special Agent in Charge and head of the bombing investigation, Sergeant John MacLellan of the Watertown (MA) Police Department who was present during the shootout on the streets of Watertown, U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts Carmen M. Ortiz, the lead prosecutor of bombing suspect Dzokhar Tsarnaev, and moderator Frank Bond, to discuss the events of that fateful day, the processes of finding and prosecuting the perpetrators, and the effects of these events on the community.

It was a crisp morning, and another world-renowned Boston Marathon was underway. No one could suspect what would happen at the finish line that afternoon. There was one blast, and then a second. According to Ms. Ortiz, “News of the explosions just spread like wildfire.”

A joint task force was able to come together quickly thanks to existing relationships among the Boston FBI Field Office, Boston PD, Massachusetts State Police, Watertown PD, and many others. Mr. DesLauriers credited all of the different departments involved in the investigation with its ultimate success. According to DesLauriers, the amount of photographic and video evidence that came in was “overwhelming,” but by focusing on videos of the finish line at Boylston Street, they were able to spot the Tsarnaev brothers. At that point, law enforcement had their primary suspects.

One stumbling block during the investigation was misreporting by the media. At one point, innocent individuals were reported as being under arrest. Rebutting this information cost both Mr. DesLauriers’s and Ms. Ortiz’s precious time. Ms. Ortiz made it clear, “As far as reliance [and] credible evidence, I rely on law enforcement.”

Another tragedy connected to the Boston bombing was the murder of MIT police officer Sean Collier, whose name is engraved on the National Law Enforcement Memorial. Mr. DesLauriers explained that he didn’t initially connect this to the marathon bombings, but after getting a call early on April 19 about a firefight on the streets of Watertown, MA, they were eventually able to connect all the dots. Sgt. MacLellan recalled chaos at the scene of the firefight in Watertown shortly after midnight. The Tsarnaev brothers were shooting at police and throwing bombs. According to Sgt. MacLellan, “This was something you couldn’t train for in our department. It was more like a war zone than a street fight.”

For the rest of the day, area residents were asked to stay in their homes as law enforcement executed a door-to-door search in Watertown. Mr. DesLauriers recalled the 911 call that ended everything the evening of April 19. “A call came in from David Henneberry who, after noticing a weather wrap was loose on his boat, looked inside and saw Dzokhar Tsarnaev alive and sleeping.”

In the end, each panelist was clearly moved by the way Boston and Watertown residents came together and the strength and resilience of the victims and their families. The relationships that were formed as a result of such tragedy was something no one will soon forget.

Thursday, September 17, 2015

One Righteous Man: Samuel Battle and the Shattering of the Color Line in New York

|

| Purchase Book |

On June 28, 1911, Samuel Jesse Battle, badge number 782, became the first black policeman in the NYPD. On that day, Police Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo told him, “You will have some difficulties, but I know you will overcome them.” Thus began Battle’s four decadelong career. Along the way Battle pushed through the ranks of the NYPD, navigated the murky waters of Tammany Hall politics, and became a founding citizen of black Harlem. Battle also pushed for equality in all of the city’s civil services, including mentoring Wesley Williams, the first black fire fighter in the New York Fire Department.

Battle’s career was never easy. He faced discrimination and threats even before taking the civil service exam, and Battle’s first day at the Twenty-Eighth Precinct was no different. He was greeted with silence, disdain, and a cot in the precinct’s flag storage loft instead of the dormitory. Years later Battle would recount his feelings to Langston Hughes, his autobiographer for a time, about enduring such abuse.

Sometimes, lying on my cot on the top floor in the silence, I would wonder how it was that many of the patrolmen in my precinct who did not yet speak English well, had no such difficulties in getting on the police force as I, a Negro American, had experienced…My name had been passed over repeatedly. All sorts of discouragements had been placed in my path. And now, after a long wait and a lot of stalling, I had finally been given a trial appointment to their ranks and these men would not speak to me. Native-born and foreign-born whites on the police force all united in looking past me as though I were not a human being. In the loft in the dark, with the Stars and Stripes, I wondered! Why?

One Righteous Man: Samuel Battle and the Shattering of the Color Line in New York is available in the Memorial Fund Gift Shop.

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

Fighting Discrimination: A Hispanic Former Agent’s Success Story

In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month (September 15 – October 15) the National Law Enforcement Museum would like to recognize the first Hispanic Special Agent in Charge (SAC) for the FBI, Bernardo ‘Mat’ Perez.

Perez served in the Bureau for 34 years. Starting in 1960 as a file clerk, he eventually obtained his degree from Georgetown University in 1963 and became an agent. In 1979, Perez was appointed SAC for the Puerto Rico Field Office. Perez successfully disregarded most discrimination, but when he was assigned to the Los Angeles Field Office in the 1980s the hostility was too overt to ignore. According to Perez, his SAC in L.A. once told him– “I’m going to overlook the fact that you’re a Mexican…that is your office and you stay over there and you don’t come out until I tell you.”

By 1987, Perez had decided he had had enough and filed a lawsuit for discrimination against the FBI. He was soon joined by 310 other Hispanic agents. In 1988, U.S. District Judge Lucius D. Bunton, found that the FBI had discriminated against Hispanics, but stressed that there was no evidence of deliberate discrimination. Bunton found that Hispanics would be given unpleasant assignments rarely tasked to their white counterparts, commonly placed as translators, even if they wanted other types of investigative work where language skills were not a factor. In an article following the decision, Perez responded, “This case proves you can fight city hall and you can win.” Despite the 1988 case being decided in favor of the agents, they were granted no monetary compensation and lost thousands of dollars in legal fees.

Acknowledging the existence of discrimination was hard for Perez. According to an article in January 2014 he said, “I had investigated Klan cross-burnings in Florida, police brutality cases in Texas, and other civil rights violations…But I refused to accept and admit that discrimination existed at my beloved FBI.” Issues of racism and discrimination had never occurred to him growing up in the small but diverse town of Lone Pine, California. He said in his oral history, “I had never seen myself as a ‘Hispanic.’ Those things didn’t exist when I was a kid. We were all ‘Americans.’”

There is no doubt that this case and his sacrifice lead to the FBI making some major changes. It also opened the door for more lawsuits to be filed against federal agencies discriminating against minorities.

*Learn more about former Special Agent Bernardo “Mat” Perez by reading his entire oral history here:

http://www.nleomf.org/museum/the-collection/oral-histories/bernardo-mat-perez.html

* Read more oral histories from the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI here: http://www.nleomf.org/museum/the-collection/oral-histories/index-2.html

Perez served in the Bureau for 34 years. Starting in 1960 as a file clerk, he eventually obtained his degree from Georgetown University in 1963 and became an agent. In 1979, Perez was appointed SAC for the Puerto Rico Field Office. Perez successfully disregarded most discrimination, but when he was assigned to the Los Angeles Field Office in the 1980s the hostility was too overt to ignore. According to Perez, his SAC in L.A. once told him– “I’m going to overlook the fact that you’re a Mexican…that is your office and you stay over there and you don’t come out until I tell you.”

|

| Book released in January about Bernardo ‘Mat’ Perez by author who joined in his lawsuit. |

Acknowledging the existence of discrimination was hard for Perez. According to an article in January 2014 he said, “I had investigated Klan cross-burnings in Florida, police brutality cases in Texas, and other civil rights violations…But I refused to accept and admit that discrimination existed at my beloved FBI.” Issues of racism and discrimination had never occurred to him growing up in the small but diverse town of Lone Pine, California. He said in his oral history, “I had never seen myself as a ‘Hispanic.’ Those things didn’t exist when I was a kid. We were all ‘Americans.’”

There is no doubt that this case and his sacrifice lead to the FBI making some major changes. It also opened the door for more lawsuits to be filed against federal agencies discriminating against minorities.

*Learn more about former Special Agent Bernardo “Mat” Perez by reading his entire oral history here:

http://www.nleomf.org/museum/the-collection/oral-histories/bernardo-mat-perez.html

* Read more oral histories from the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI here: http://www.nleomf.org/museum/the-collection/oral-histories/index-2.html

Wednesday, August 12, 2015

True Stories of Former G-men

This month, Museum staff was excited to delve into some of the rich stories that exist in our FBI Oral History Collection. In honor of the upcoming release of our Executive Director, Joe Urschel’ s book, The Year of Fear: Machine Gun Kelly and the Manhunt that Changed the Nation, we thought it would be fun to highlight some stories from FBI Agents who worked during that era. That is – the era of gangsters like Machine Gun Kelly, John Dillinger, the Barker-Karpis gang, and all the other’s that J. Edgar Hoover and his G-men sought to bring down.

CK: I think on Labor Day in September of 1933, as another example of calls we received on holidays, Frank Blake, who was the Agent in Charge of the Dallas FBI Office, called and said, “Is Mr. Hoover there?” And I said, “No.” “Well, ya better get in touch with him because Harvey Bailey escaped from the Dallas County Jail today.” Harvey Bailey was one of the kidnappers arrested in connection with the kidnapping of Charles Ersal [sic] of Oklahoma City. So the Director immediately came down to the office and I started making calls to all the various Field Offices, advising them that Bailey escaped. However, we subsequently received a call from Blake that they had apprehended him about six hours later. But that is typical of the types of calls that we received over weekends, holidays, or at nighttime.

Interviewer: Excuse me, Charles. Now, you said when you received one of these calls that this person escaped from jail, you were then going to call up other Field Offices by telephone and advise them to be on the lookout?

CK: That is correct.

Well he immediately knew what had happened, so the next day, while he was out to lunch, he stopped by someplace and bought a little toy red fire engine and gave it to Helen Gandy and said, “This is for future emergencies, Helen.”

Interviewer: Uh huh, that was when you were in Chicago?

JW: Chicago. Daddy was in the alley to shoot, but Dillinger didn’t make it but it was daddy’s turn next to try…And I remember that because he came home; we had a luxurious one bedroom apartment (laughing). They slept in the living room on, you know, a hide-a-bed then and I could remember him coming home and saying, “We shot that son of a bitch.”

Interviewer: Uh huh.

JW: “He” was Dillinger.

Interviewer: Yeah, yeah. Well that was a, that was a long running duel there over, over the years. So he was actually there and he was in the, you said he was in an alley?

JW: Yeah in the theater alley…When they shot him.

Interviewer: …Right and the lady in red and there’s about seventeen people who’ve claimed that shot Dillinger.

JW: (Laughing)

Interviewer: But your father didn’t?

JW: No (laughing).

Find stories like this from over 200 FBI agents on our website. Check them out here: http://www.nleomf.org/museum/the-collection/oral-histories/oral-histories-1.html.

|

| Collection of the National Law Enforcement Museum, 2010.11 |

Excerpts from Interview with Charles E. Kleinkauf (Agent from 1931-1963)

At headquarters after the Urschel Kidnapping ...

CK: I think on Labor Day in September of 1933, as another example of calls we received on holidays, Frank Blake, who was the Agent in Charge of the Dallas FBI Office, called and said, “Is Mr. Hoover there?” And I said, “No.” “Well, ya better get in touch with him because Harvey Bailey escaped from the Dallas County Jail today.” Harvey Bailey was one of the kidnappers arrested in connection with the kidnapping of Charles Ersal [sic] of Oklahoma City. So the Director immediately came down to the office and I started making calls to all the various Field Offices, advising them that Bailey escaped. However, we subsequently received a call from Blake that they had apprehended him about six hours later. But that is typical of the types of calls that we received over weekends, holidays, or at nighttime.

Interviewer: Excuse me, Charles. Now, you said when you received one of these calls that this person escaped from jail, you were then going to call up other Field Offices by telephone and advise them to be on the lookout?

CK: That is correct.

Purvis Press Conference…

CK: …Well, now that you’ve mentioned Miss Gandy [Director Hoover’s personal secretary], let’s go forward a little bit. In July of 1934, on a Sunday evening, I received a telephone call from Melvin Purvis that they had succeeded in killing John Dillinger. So I immediately telephoned the Director. He came down to the office; while he was coming to the office, I called a number of the news reporters who covered the Department of Justice, and the Director held a press conference that evening, in his office, about the capture of John Dillinger. So follow that up, a month or so later, Melvin Purvis came to Washington for a conference with the Director, which began sometime in the late afternoon. It got to be about 5:20, which was 20 minutes beyond when the Director and everybody usually went home. So Helen Gandy came to the door of the file room, which was directly across from the Director’s door, and said, “Can’t we do something to break up this conference?” Howard Kennedy, another night clerk, and I were working at that time, and Howard got up outside the Director’s door and yelled, “Fire! Fire!” And the door opened and Purvis came out in the hall and the Director said, “Where is the fire, boys?” And we said, “We’re sorry Mr. Hoover, we didn’t hear anything but we’ll check for you right away.” That broke up the conference.

Well he immediately knew what had happened, so the next day, while he was out to lunch, he stopped by someplace and bought a little toy red fire engine and gave it to Helen Gandy and said, “This is for future emergencies, Helen.”

|

| Collection of the National Law Enforcement Museum, 2010.11 |

Excerpt from Interview with Jeanne S. Willcut, daughter of Raymond Suran (Agent from 1930-1955)

The night Dillinger was shot…

JW: Well, I remember the night that Dillinger was killed.

Interviewer: Uh huh, that was when you were in Chicago?

JW: Chicago. Daddy was in the alley to shoot, but Dillinger didn’t make it but it was daddy’s turn next to try…And I remember that because he came home; we had a luxurious one bedroom apartment (laughing). They slept in the living room on, you know, a hide-a-bed then and I could remember him coming home and saying, “We shot that son of a bitch.”

Interviewer: Uh huh.

JW: “He” was Dillinger.

Interviewer: Yeah, yeah. Well that was a, that was a long running duel there over, over the years. So he was actually there and he was in the, you said he was in an alley?

JW: Yeah in the theater alley…When they shot him.

Interviewer: …Right and the lady in red and there’s about seventeen people who’ve claimed that shot Dillinger.

JW: (Laughing)

Interviewer: But your father didn’t?

JW: No (laughing).

Find stories like this from over 200 FBI agents on our website. Check them out here: http://www.nleomf.org/museum/the-collection/oral-histories/oral-histories-1.html.

Friday, July 10, 2015

Tag is On the Case

The Museum’s Teacher Advisory Group (TAG) had a unique meeting in April. William Greene, Director of Technical Operations for Prince George’s County Police Crime Scene Investigation Division, presented an interactive forensics class for TAG members. Greene put the educators in the role of student investigators by preparing a mock crime scene that the teachers then had to solve. The experience sparked the group’s imagination and made for an exciting follow-up meeting in June.

TAG members listening to William Greene

In the Museum, Take the Case will invite visitors to explore different crime solving techniques including forensic analysis of ballistics, DNA, and trace evidence. TAG developed several field trip lesson plans for the Take the Case exhibit in the Museum based on their mock crime scene experience. The TAG members split into four groups and developed unique lesson plans that looked at different aspects of the exhibit. Two groups focused on field trips for different grade levels to learn about and explore the significance of the Miranda Rights. Students were directed to question what rights are, how they are implemented in America, and whether the Miranda Rights are still necessary. The other two groups had students think creatively about crime solving through narrative writing and the scientific process.

TAG is composed of primary and secondary school educators who teach in public and private schools in Washington, DC; Maryland; and Virginia. The educators work collaboratively with staff to analyze future Museum’s exhibits and develop related field trip ideas and museum educational resources for use in the classroom. TAG is on break until next school year when they will continue to explore new ways for students to interact with the National Law Enforcement Museum’s objects and exhibits.

Thursday, April 16, 2015

Artifact Spotlight: Cecil Kirk, JFK Assassination Related Archive

Officer Cecil Kirk providing testimony to the House Select Committee on Assassinations.

Collection of the National Law Enforcement Museum, 2015.2.6. |

The National Law Enforcement Museum is pleased to announce the acquisition of a fascinating archive of materials from the estate of Officer Cecil Kirk of the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, DC.

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, it shook the nation and sparked a chain of events that would have countless implications for law enforcement. President Johnson established the Warren Commission to do a full investigation of the assassination. Public response to the Warren Commission’s final report was widespread skepticism, and a variety of conspiracy theories began to circulate surrounding evidence from the case.

In response to this prevalent distrust, in 1976, the United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was formed to further investigate the Kennedy assassination, as well as the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Officer Kirk was tasked with providing the Committee an analysis of the forensic photography and photographic documentation of the JFK investigation. This included providing testimony to the Committee on Lee Harvey Oswald’s infamous “backyard photographs,” which many in the public had begun to think were fabricated. Through his work and testimony, Kirk and his team confirmed the authenticity of these photos.

Varying examples of the Lee Harvey Oswald’s infamous backyard photograph. Kirk made prints from the photograph’s original negative to present as part of his testimony. Collection of the National Law Enforcement Museum, 2015.2.3.

The archive includes copies of Kirk’s testimony to the HSCA with his hand written notes, as well as examples of some of the photographs he used to make his case.

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Jana Monroe: Oral History

Jana Monroe never waited for an invitation. As one of the first female sworn officers in California policing, Monroe was “pretty much an anomaly” in her own words. At first she was given traditionally feminine roles – looking after children at an arrest, dealing with juvenile offenders, and talking to female victims, but Monroe wanted more out of the job.

Jana Monroe never waited for an invitation. As one of the first female sworn officers in California policing, Monroe was “pretty much an anomaly” in her own words. At first she was given traditionally feminine roles – looking after children at an arrest, dealing with juvenile offenders, and talking to female victims, but Monroe wanted more out of the job. “I would always volunteer,” recalled Monroe, “So, somebody [would ask] want to put the handcuffs on? Want to make the arrest? W[ant] to do the interview? I always was willing…” It was that willingness to do anything and everything that allowed Monroe to get so much experience in her first years as a police officer. She worked the “gamut” of violations from gang work to homicides to fraud cases.

In 1973, the FBI, under a new director, allowed women to enter the ranks of special agent. Monroe was interested in the challenges of being a federal officer, but her then husband was against the idea. When she planned to enter the academy, he gave her an ultimatum, “It’s either me or the FBI.” Monroe’s response was simple, “Okay, I’m going in the FBI.”

Monroe was assigned to the Tampa, Florida office—a bank robbery hotspot at that time. She remembers, “We had probably seven to eight bank robberies a week.” The Reactive Squad was the primary unit assigned to these dangerous cases. Of course, Monroe saw it as the squad to be on and approached the Special Agent in Charge (SAC). “Well, we’ve never had a female on it before,” was his response to which she said, ‘That doesn’t sound like a good reason to me.”

While Monroe was enjoying the high-intensity cases with the Reactive Squad, her goal was always to serve in the FBI’s prestigious Behavioral Science Unit (BSU). In the 1990s, Monroe became the first female BSU special agent working alongside John Douglas and Roy Hazelwood. The BSU used the “think tank” approach to profile serial, mass and spree type killers. It’s become recognizable today from movies like Silence of the Lambs and TV shows like Criminal Minds. Of the work she said, “I think if you look at serial killer behavior…it’s something that’s compelling and repulsive at the same time.”

Monroe held several administrative FBI positions before retiring to the private sector. For women in law enforcement, Monroe sees much more opportunities than in the early days. “I think the extreme proving of oneself that I know I need[ed] to go through…in the pioneer time, it’s dissipated.” Today, Monroe encourages the female law enforcement officers she mentors to volunteer for jobs just like she did. Read Jana Monroe’s full interview and find more first-hand accounts of law enforcement history in our Museum Oral History Collection.

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Dr. Cedric Alexander: Oral History

These were the words that allowed Cedric Alexander at the age of 19, a college drop-out, and new father to get his start in law enforcement. In a recent oral history interview, Alexander, now the chief safety officer for DeKalb County, Georgia and the president of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE), described his conversation with Sheriff Raymond Hamlin as a defining moment in his life.

In 1970s Florida if someone wanted to attend the police academy, they would either have to already have a job with a Florida police department or pay $100 and get a police chief or sheriff to sign off on their paperwork. For Alexander, Sheriff Hamlin was his last chance. “I didn’t even know how to dress for an interview,” recalled Alexander, “I went over there in a jean jacket, jeans, [and] a skull cap, like a typical college student.” Hamlin had a “reputation of being a sexist and a racist and a bigot”, but the two men found common ground. After two and half hours of talking, Hamlin signed Alexander’s paperwork and they went their separate ways, yet Alexander says, “Everything in my career over the last 37 years is because Sheriff Raymond Hamlin opened the door and gave me an opportunity that nobody else would.”

Alexander’s conversation with Sheriff Hamlin paved his way into the police academy and local law enforcement. Now as a law enforcement official, Alexander encourages everyone to take a second look at people and try to truly follow Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s lesson of judging people by the content of their character and not by first impressions. The challenges of being a black man in the United States are keenly felt by Alexander who is all too aware of the precarious tight rope African-American officers must walk in their communities. He says, “It’s a double-edge sword for a black police officer because… you’ve got to be sensitive to the struggles and history in your own population, but you also are tied to the responsibilities and the oath that you’ve taken as a law enforcement official.”

The need for racial sensitivity in hiring, policing, and training will be foremost in Alexander’s thoughts as he works in his community and on a national stage in President Obama’s new task force on 21st Century Policing. But Alexander’s expectations for his officers are the same for all the law enforcement executives he encounters, “we maintain law and order, do what we’re sworn to do…we’re aware of [our biases and prejudices]…and we treat everybody the same regardless.” Read Dr. Alexander’s full interview and find more first-hand accounts of law enforcement history in our Museum Oral History Collection, sponsored by Target®.

Wednesday, January 14, 2015

Exciting New Object for Museum Exhibit

|

|

While monster-like in appearance,

this suit is an incredible feat of technology.

Collection of the National Law Enforcement Museum.

2014.13. |

When a bomb tech needs to render safe an explosive by hand, the explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) suit, or bomb suit, provides the best defense. A combination of rigid and soft armor protects against the two main threats of an explosion – the overpressure wave (shockwave) and shrapnel. What else is this suit capable of? Take a look:

Helmet

To prevent overheating, a tube lets outside air flow into the helmet, which also has an internal cooling device.

Visor

Protects the face from shockwaves and shrapnel while still allowing the tech to see clearly.

Collar

Ensures that a tech’s head and neck are completely covered no matter how they move their body.

Body Armor

Armor plates protect the torso, groin and thighs. Techs can configure their armor to provide more or less protection in specific areas of the body.

Front

Where the most protection is concentrated. Accordingly, techs train to face an explosive at all times even if that means walking backwards.

Hands and Feet

Techs rarely wear gloves, as hand dexterity is critical. Protective foot coverings can be attached at the tech’s discretion.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)