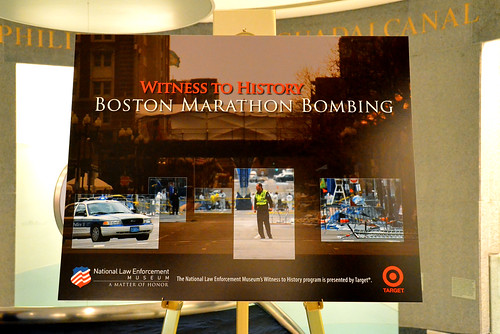

National Law Enforcement Museum’s Panel discussion examined the events of the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombing investigation and its impact on the community.

It was only two and a half years ago on April 15, 2013, that two explosions at the finish line of the Boston Marathon shook the nation and changed the lives of so many. On Wednesday, October 7, 2015 the National Law Enforcement Museum brought together Richard DesLauriers, former Boston FBI Special Agent in Charge and head of the bombing investigation, Sergeant John MacLellan of the Watertown (MA) Police Department who was present during the shootout on the streets of Watertown, U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts Carmen M. Ortiz, the lead prosecutor of bombing suspect Dzokhar Tsarnaev, and moderator Frank Bond, to discuss the events of that fateful day, the processes of finding and prosecuting the perpetrators, and the effects of these events on the community.

It was a crisp morning, and another world-renowned Boston Marathon was underway. No one could suspect what would happen at the finish line that afternoon. There was one blast, and then a second. According to Ms. Ortiz, “News of the explosions just spread like wildfire.”

A joint task force was able to come together quickly thanks to existing relationships among the Boston FBI Field Office, Boston PD, Massachusetts State Police, Watertown PD, and many others. Mr. DesLauriers credited all of the different departments involved in the investigation with its ultimate success. According to DesLauriers, the amount of photographic and video evidence that came in was “overwhelming,” but by focusing on videos of the finish line at Boylston Street, they were able to spot the Tsarnaev brothers. At that point, law enforcement had their primary suspects.

One stumbling block during the investigation was misreporting by the media. At one point, innocent individuals were reported as being under arrest. Rebutting this information cost both Mr. DesLauriers’s and Ms. Ortiz’s precious time. Ms. Ortiz made it clear, “As far as reliance [and] credible evidence, I rely on law enforcement.”

Another tragedy connected to the Boston bombing was the murder of MIT police officer Sean Collier, whose name is engraved on the National Law Enforcement Memorial. Mr. DesLauriers explained that he didn’t initially connect this to the marathon bombings, but after getting a call early on April 19 about a firefight on the streets of Watertown, MA, they were eventually able to connect all the dots. Sgt. MacLellan recalled chaos at the scene of the firefight in Watertown shortly after midnight. The Tsarnaev brothers were shooting at police and throwing bombs. According to Sgt. MacLellan, “This was something you couldn’t train for in our department. It was more like a war zone than a street fight.”

For the rest of the day, area residents were asked to stay in their homes as law enforcement executed a door-to-door search in Watertown. Mr. DesLauriers recalled the 911 call that ended everything the evening of April 19. “A call came in from David Henneberry who, after noticing a weather wrap was loose on his boat, looked inside and saw Dzokhar Tsarnaev alive and sleeping.”

In the end, each panelist was clearly moved by the way Boston and Watertown residents came together and the strength and resilience of the victims and their families. The relationships that were formed as a result of such tragedy was something no one will soon forget.